[ad_1]

The transient’s key findings are:

- Black owners have much less housing wealth than White owners. This research explores the explanations for the wealth hole at age 55.

- Black owners confronted obstacles at each step – from accumulating a down fee to purchasing in engaging areas to accessing credit score to upsize.

- The evaluation compares related Black and White households to see what share of the wealth hole is as a result of early hurdles vs. slower appreciation.

- The outcomes present that each components – smaller down funds and slower development in dwelling values – have been equally essential contributors to the hole.

Introduction

Homeownership is likely one of the largest sources of retirement wealth for many households and is promoted as a key device for wealth accumulation. Nonetheless, an extended historical past of discrimination within the housing market has constrained the flexibility of Black households to build up housing wealth relative to their White counterparts. Consequently, Black households approaching retirement are much less prone to personal houses and, after they do, they see decrease wealth accumulation in comparison with White owners. This transient, which is predicated on a current paper, focuses on the owners.

The aim is to find out what share of the age-55 housing wealth hole is because of drawback on the time of first buy – specifically, much less parental help with the mortgage down fee – and what share is because of slower appreciation of subsequent housing wealth? To isolate the influence of those components, the evaluation compares older Black and White owners who appear equally in a position to accumulate housing wealth based mostly on their socioeconomic traits, however who nonetheless ended up with completely different outcomes.

The dialogue proceeds as follows. The primary part gives background on how older Black households confronted drawback in practically each side of the housing market. The second part outlines the info and methodology used to judge the racial housing wealth hole over the lifecycle for in any other case related owners. The third part presents the outcomes, which present that each components – disparities at first buy and subsequent appreciation – play an essential function in explaining the hole at age 55. The ultimate part concludes that future analysis ought to think about how structural adjustments within the housing market over the previous 30 years may need alleviated some boundaries for youthful homebuyers.

Background

The reason for the racial housing wealth hole amongst households approaching retirement begins early within the lifecycle. Decrease family incomes hinder the flexibility of Black households to avoid wasting for a down fee and entry the monetary companies wanted to buy a primary dwelling. Even amongst households with related revenue, Black households usually lack generational wealth, making them much less prone to obtain help from their dad and mom on a down fee. Earlier research discover that younger White households are 3 times as doubtless as Black households to obtain parental help for a house buy, leading to the next mortgage approval charge and facilitating homeownership at a barely youthful age. Furthermore, older Black households confronted pervasive discrimination in mortgage lending through the Eighties and Nineteen Nineties, though current proof exhibits that discriminatory lending has largely abated on account of elevated regulation and widespread adoption of automated underwriting programs.

When Black households ultimately transition into homeownership, they’re constrained to buy much less invaluable first houses. Along with having a smaller down fee, Black households are hardly ever in a position to buy houses with the identical facilities as White households due to historic redlining that pushed Black households into segregated neighborhoods with much less public funding. Residential segregation not solely limits the acquisition value of Black houses, but in addition depresses subsequent development within the worth of the home. Since households usually dwell in the identical home for lengthy intervals, slower appreciation results in a lot decrease compounding and in the end, decrease housing values.

Lastly, Black households usually tend to promote or lose their dwelling, a phenomenon that was significantly stark through the monetary disaster of 2008. Certainly, one current research argues that disparities in distressed dwelling gross sales clarify many of the racial hole in appreciation charges. Nonetheless, for the reason that aim right here is to judge the racial housing wealth hole between owners approaching retirement, households who lose their home drop out of our pattern solely.

Provided that Black households face drawback in practically each side of the housing market, this transient asks a easy query: what share of the housing wealth hole amongst older Black and White owners is because of disparities on the time of first buy, and what share is because of slower appreciation over the course of homeownership?

Knowledge and Methodology

This evaluation depends on the Panel Examine of Earnings Dynamics (PSID), a nationally consultant survey carried out since 1968, which incorporates in depth info on homeownership and housing wealth accumulation, and race. The evaluation focuses on Black and White households who purchase their first dwelling between 1980-2000 and follows them by 2019, limiting the pattern to those that are nonetheless owners at age 55.

The aim is to match older Black and White owners who, based mostly on their very own socioeconomic traits, might sound equally properly located to build up housing wealth. The extent to which Black households fall brief on this comparability displays two sources of structural drawback: the shortage of parental help and chronic discrimination within the housing market. The evaluation regresses housing wealth at preliminary buy and age 55 (measured in logs and web of mortgage debt) on family revenue and different demographic traits:

Housing wealth = ƒ(Black, log revenue, family demographics)

The unbiased variable of curiosity is the Black indicator, which displays the racial hole in housing wealth holding revenue and demographics fixed. To current the outcomes from these regressions in an intuitive means, the coefficients are used to simulate housing wealth for hypothetical Black and White households who’re assumed to have the identical traits (chosen to be consultant of the PSID pattern).

Outcomes

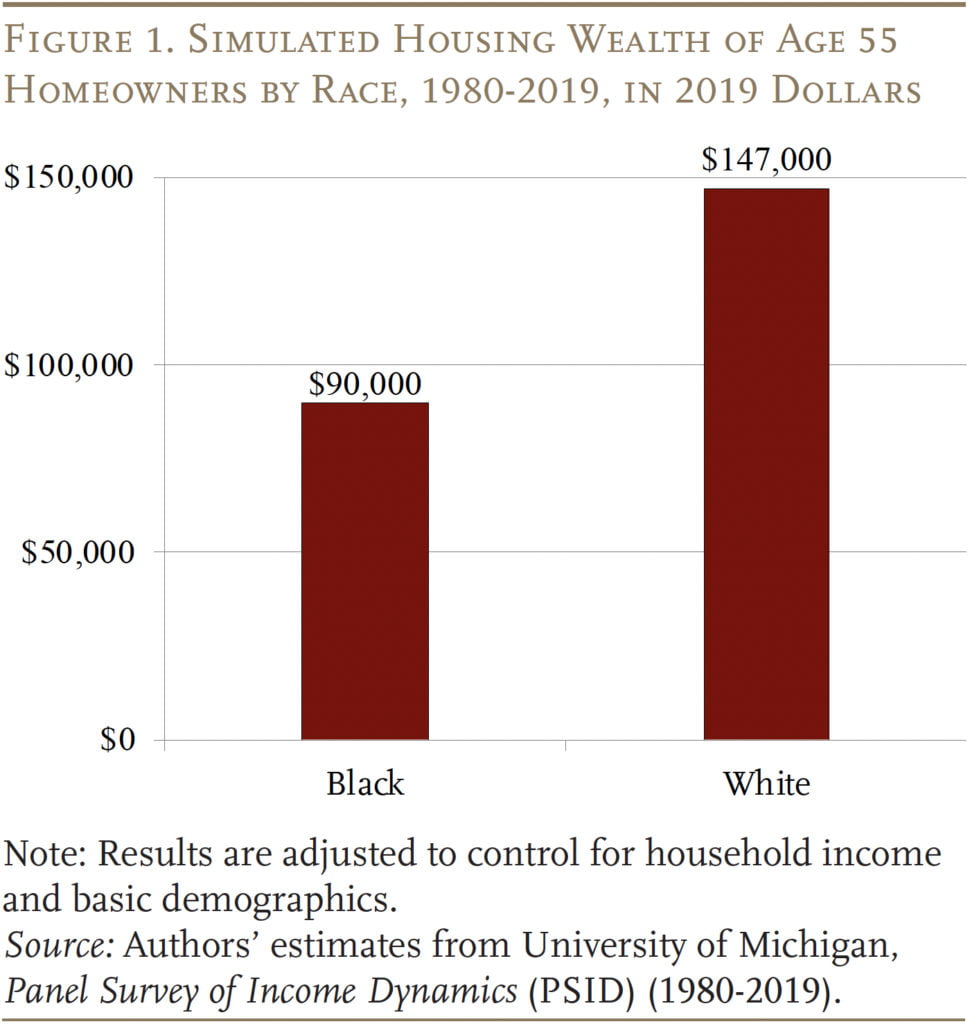

To set the stage for the primary outcomes, Determine 1 compares housing wealth at age 55 for the hypothetical Black and White households. As anticipated, after controlling for revenue and fundamental demographics, Black owners approaching retirement have solely 61 % of the housing wealth held by older White owners.

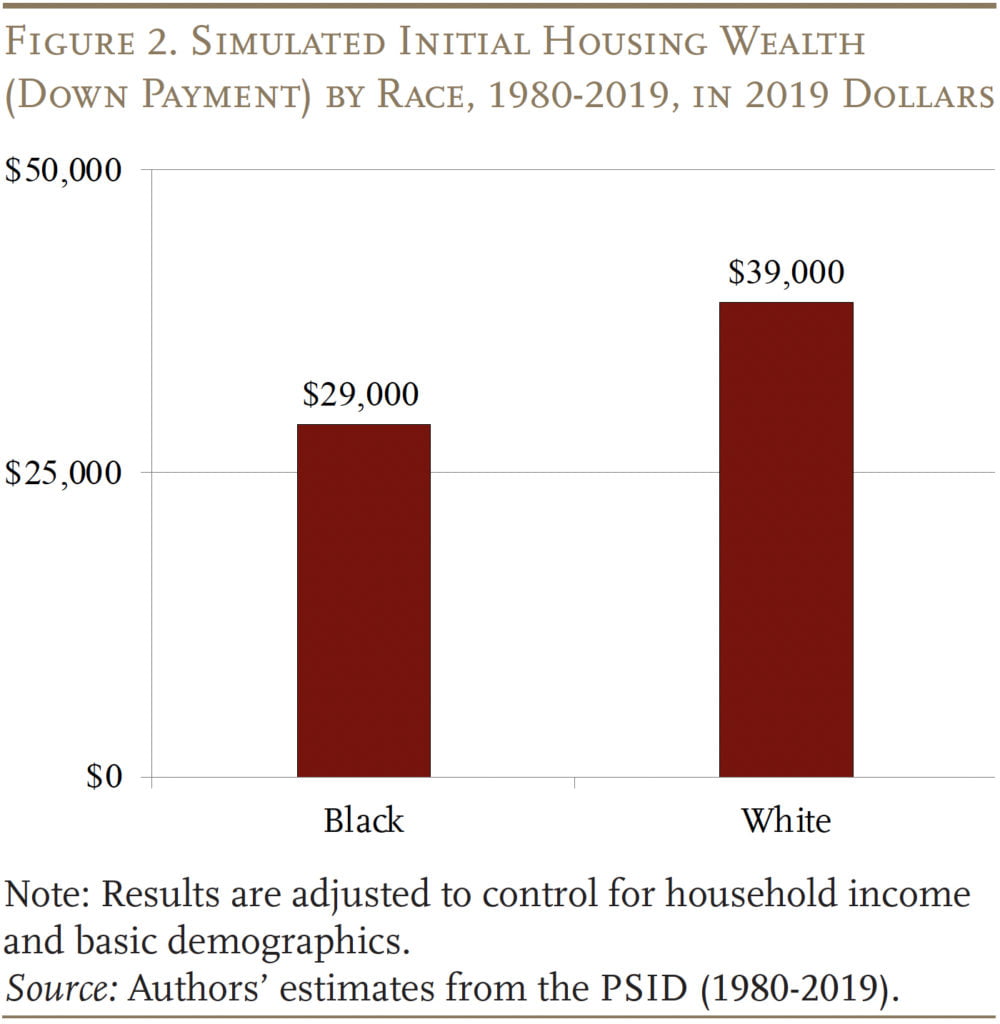

To know the drivers of this hole, step one is to contemplate housing market experiences in younger maturity. Preliminary housing wealth is just the family’s down fee (first home value much less mortgage principal); as anticipated, Black households approached the housing market with fewer sources to take a position. Particularly, preliminary housing wealth for Black households was solely 74 % of preliminary wealth for his or her otherwise-similar White counterparts (see Determine 2).

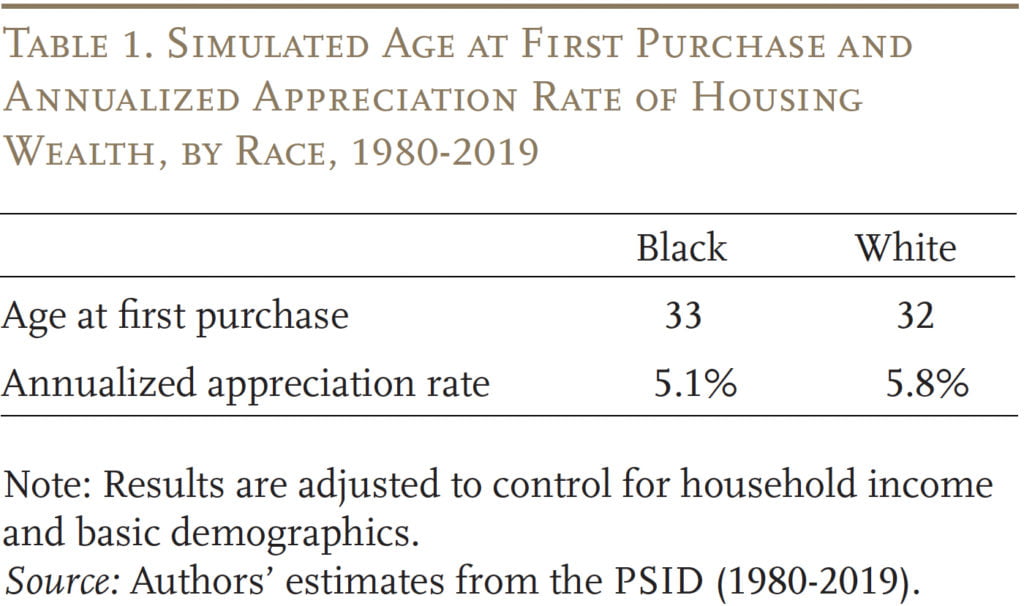

Due to this useful resource deficit, Black households ended up shopping for cheaper first houses than White households. Additionally they purchased them barely later (see first row of Desk 1). Consequently, Black households had rather less time to see their homes develop in worth and pay down their debt earlier than age 55.

Not solely did older Black owners begin from a weaker place, however their housing wealth additionally grew extra slowly over time. The second row of Desk 1 calculates the interior charge of return that, when utilized to the down fee, yields housing wealth at age 55. For each Black and White owners, this inside charge of return exceeds the annual appreciation charge of the home itself (round 2 % throughout this era) as a result of housing is a extremely leveraged funding. However, Black housing wealth grew 0.7 share factors slower per yr. Compounded over twenty years, this annual appreciation penalty explains many of the cumulative distinction within the development of housing wealth.

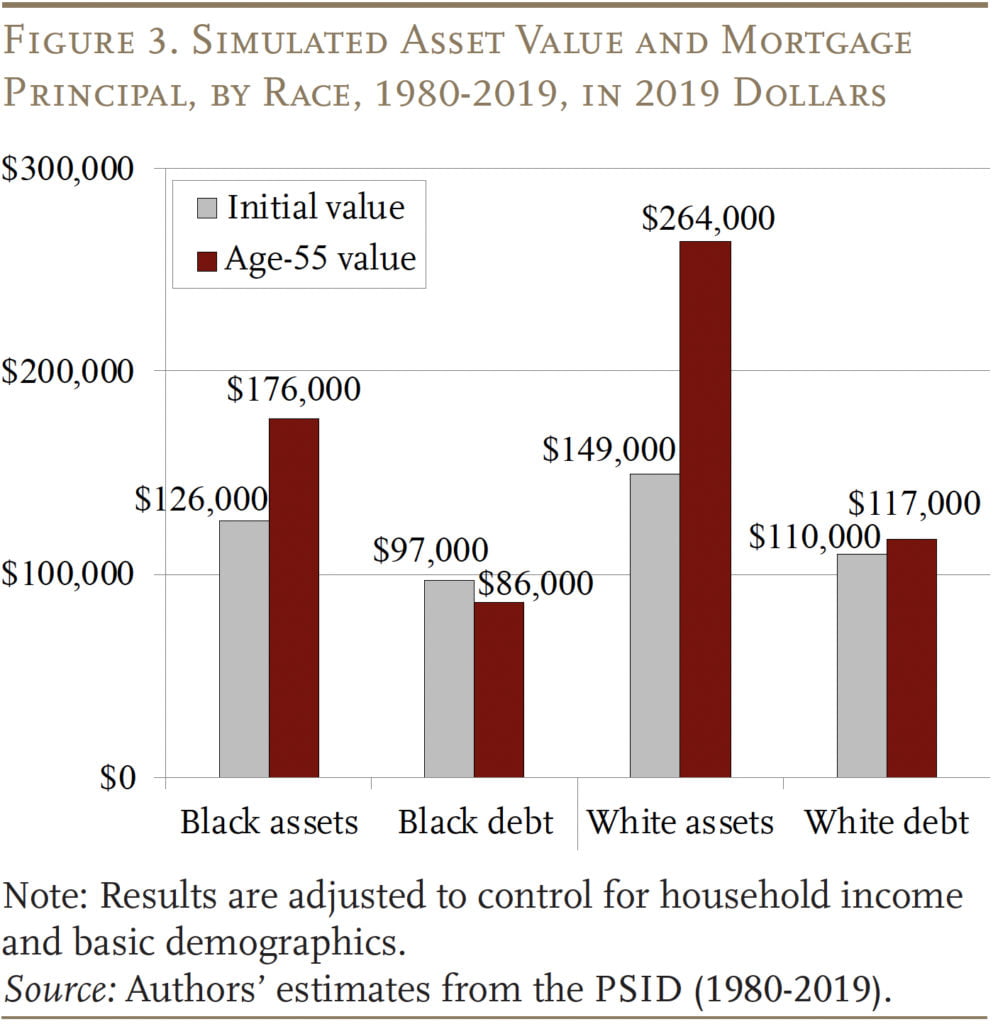

From a coverage perspective, one may surprise what brought about such a stark distinction in appreciation: weak development within the worth of Black-owned houses, or slower amortization of mortgage debt? Therefore, Determine 3 breaks wealth into its parts: the asset worth of the home and the remaining mortgage principal. On the asset aspect, the worth of Black-owned houses grew by solely 40 % (from $126,000 to $176,000), in comparison with 77 % for houses owned by White households (from $149,000 to $264,000). On the debt aspect, remaining mortgage principal dropped by 11 % for Black households, however truly grew barely for White households between the time of first buy and age 55.

The expansion in debt for White households could appear stunning on condition that, by age-55, households had been making mortgage funds for twenty years. It seems that many older households traded their “starter dwelling” for a bigger, extra invaluable home with greater appreciation, and financed the acquisition with further debt. Black households have been 26 % much less prone to benefit from this leveraged upsizing. And after they did, they borrowed much less. As well as, older White households have been extra prone to refinance their authentic mortgage as rates of interest fell, and a few of these transactions have been cash-out refinances. Though they’re occasionally mentioned within the literature on mortgage lending, each of those components recommend that racial boundaries to accessing credit score persevered over the lifecycle for this cohort of older owners.

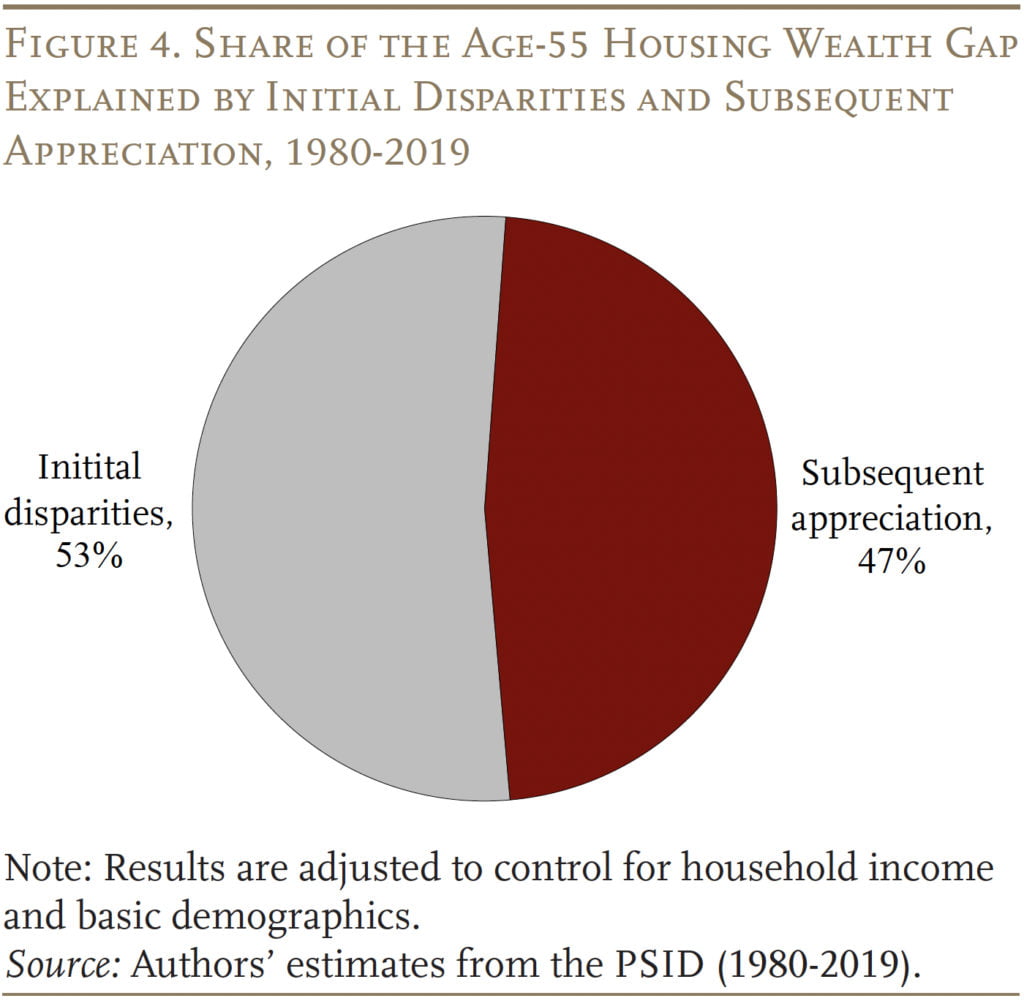

Finally, the aim of this transient is to find out what share of the age-55 wealth hole is pushed by preliminary disparities, and what share is because of subsequent appreciation. In order a last train we conduct a thought experiment: how massive would the age-55 hole have been had Black households began off with the identical preliminary housing wealth as White households, however then subsequently earned their precise, decrease appreciation charge? Determine 4 presents the outcomes, with preliminary disparities accounting for 53 % of the particular hole and slower appreciation producing the opposite 47 %. Nonetheless, the precise share is delicate to how the thought experiment is framed.

Conclusion

Black households face drawback in practically each side of the housing market. Consequently, Black households approaching retirement are much less prone to personal houses than White households; and even amongst owners with related family revenue and demographics, older Black households have much less housing wealth than their White counterparts. Therefore, this transient addressed a easy query: what share of the housing wealth hole at age 55 is because of adversarial experiences on the time of first buy – specifically, fewer sources to assist a down fee – and what share is because of slower appreciation in subsequent years? Though the precise reply is considerably delicate to the small print of the evaluation, the conclusion is obvious – every issue contributed meaningfully to the age-55 hole.

Closing the housing wealth hole is a posh drawback to resolve. Nonetheless, in a minimum of one side of the housing market – mortgage lending – situations appear to be enhancing for younger Black homebuyers. Therefore, future analysis ought to think about how structural adjustments within the housing market over the previous 30 years may cut back the age-55 housing wealth hole transferring ahead.

References

Aaronson, Daniel, Daniel Hartley, and Bhashkar Mazumder. 2021. “The Results of the Nineteen Thirties HOLC ‘Redlining’ Maps.” American Financial Journal: Financial Coverage 13(4): 355-392.

Amornsiripanitch, Natee. 2020. “Why Are Residential Property Tax Charges Regressive?” Working Paper 22-02. Philadelphia, PA: Federal Reserve Financial institution of Philadelphia.

Avenancio-León, Carlos F. and Troup Howard. 2022. “The Evaluation Hole: Racial Inequalities in Property Taxation.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 137(3): 1383-1434.

Bartlett, Robert, Adair Morse, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace. 2022. “Shopper-lending Discrimination within the FinTech Period.” Journal of Monetary Economics 143(1): 30-56.

Bayer, Patrick, Marcus Casey, Fernando Ferreira, and Robert McMillan. 2017. “Racial and Ethnic Value Differentials within the Housing Market.” Journal of City Economics 102(November): 91-105.

Bayer, Patrick, Fernando Ferreira, and Stephen L. Ross. 2016. “The Vulnerability of Minority Householders within the Housing Growth and Bust.” American Financial Journal: Financial Coverage 8(1): 1-27.

Berry, Christopher R. 2021. “Reassessing the Property Tax.” Working Paper. Chicago, IL: College of Chicago, Harris College of Public Coverage.

Bhutta, Neil, Aurel Hizmo, and Daniel Ringo. 2022. “How A lot Does Racial Bias Have an effect on Mortgage Lending? Proof from Human and Algorithmic Credit score Choices.” Finance and Economics Dialogue Collection 2022-067. Washington, DC: U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Bond, Shaun A. and Michael D. Eriksen. 2021. “The Position of Mother and father on the Dwelling Possession Expertise of Their Youngsters: Proof from the Well being and Retirement Examine.” Actual Property Economics 49(2): 433-458.

Charles, Kerwin Kofi and Erik Hurst. 2002. “The Transition to Dwelling Possession and the Black-White Wealth Hole.” The Overview of Economics and Statistics 84(2): 281-297.

Choi, Jung Hyun and Laurie Goodman. 2018. “Purchase Younger, Earn Extra: Shopping for a Home Earlier than Age 35 Provides Householders Extra Bang for Their Buck.” Washington, DC: City Institute.

Choi, Jung Hyun, Alanna McCargo, and Laurie Goodman. 2019. “Three Variations Between Black and White Homeownership That Add to the Housing Wealth Hole.” Washington, DC: City Institute.

Di, Zhu Xiao, Eric Belsky, and Xiaodong Liu. 2007. “Do Householders Obtain Extra Family Wealth within the Lengthy Run?” Journal of Housing Economics 16(3-4): 274-290.

Faber, Jacob. 2021. “Up to date Echoes of Segregationist Coverage: Spatial Marking and the Persistence of Inequality.” City Research 58(5): 1067-1086.

Ihlanfeldt, Keith and Tom Mayock. 2009. “Value Discrimination within the Housing Market.” Journal of City Economics 66(2): 125-140.

Kermani, Amir and Francis Wong. 2021. “Racial Disparities in Housing Returns.” Working Paper 29306. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Lee, Hyojung, Dowell Myers, Gary Painter, Johanna Thunell, and Julie Zissimopoulos. 2020. “The Position of Parental Monetary Help within the Transition to Homeownership by Younger Adults.” Journal of Housing Economics 47(March): 101597.

Liu, Siyan and Laura D. Quinby. 2023. “What Components Drive Racial Disparities in Housing Wealth Accumulation?” Working Paper 2023-3. Chestnut Hill, MA; Middle for Retirement Analysis at Boston Faculty.

Markley, Scott N., Taylor J. Hafley, Coleman A. Allums, Steven R. Holloway, and Hee Cheol Chung. 2020. “The Limits of Homeownership: Racial Capitalism, Black Wealth, and the Appreciation Hole in Atlanta.” Worldwide Journal of City and Regional Analysis 44(2): 310-328.

Mayock, Tom and Rachel Spritzer Malacrida. 2018. “Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities within the Monetary Returns to Homeownership.” Regional Science and City Economics 70: 80-96.

Munnell, Alicia H., Geoffrey M. B. Tootell, Lynn E. Browne, and James McEneaney. 1996. “Mortgage Lending in Boston: Decoding HMDA Knowledge.” The American Financial Overview 86(1): 25-53.

Myers, Caitlin Knowles. 2004. “Discrimination and Neighborhood Results: Understanding Racial Differentials in US Housing Costs.” Journal of City Economics 56(2): 279-302.

Neal, Michael, Jung Hyun Choi, and John Walsh. 2020. “Earlier than the Pandemic, Householders of Shade Confronted Structural Boundaries to the Advantages of Homeownership.” Washington, DC: City Institute.

Newman, Sandra J. and C. Scott Holupka. 2015. “Is Timing All the pieces? Race, Homeownership and Web Value within the Tumultuous 2000s.” Actual Property Economics 44(2): 307-354.

College of Michigan. Panel Survey of Earnings Dynamics, 1980-2019. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Analysis, Survey Analysis Middle.

Zonta, Michela. 2019. “Racial Disparities in Dwelling Appreciation.” Washington, DC: Middle for American Progress.

[ad_2]