[ad_1]

The transient’s key findings are:

- A standard concern is that an growing old workforce will scale back productiveness and agency profitability, but the proof so far is blended.

- This evaluation examines the problem utilizing a big pattern from the newest out there Census knowledge that hyperlinks workers to their employers.

- The outcomes present little proof that older employees scale back productiveness or profitability, though vast variation by trade exists.

- Thus, concern about an growing old workforce hampering financial efficiency could also be overblown.

Introduction

The U.S. workforce is quickly growing old, spurring widespread concern over the implications of older employees for the economic system at giant, and for companies particularly. Discrimination in opposition to older employees in hiring, and employer issues in regards to the excessive price of older employees, counsel that employers view them as much less helpful than their youthful counterparts. But, the proof from earlier than the flip of the century is decidedly blended, and up to date analysis on older U.S. employees tends to take a look at worker motivation and engagement, relatively than exhausting measures of agency efficiency. Subsequently, the productiveness and profitability of using older employees stay an open query.

This transient, which is predicated on a latest paper, makes use of restricted U.S. Census Bureau knowledge to narrate quantitative measures of employee worth – productiveness (income per employee) and profitability (income divided by wages) – to the age distribution of the agency’s workers. Along with a descriptive evaluation, this research gives quasi-experimental proof to get at a causal relationship between the age construction of the workforce and the end result measures.

The dialogue proceeds as follows. The primary part summarizes the literature on the enterprise worth of older employees. The second part describes the information and the strategies for the 2 analyses, whereas the third and fourth sections current the outcomes. The ultimate part concludes that, based mostly on our evaluation, no assist exists for the notion that older employees are much less productive than their youthful counterparts, and the proof for any adverse affect on profitability is weak. Therefore, concern about an growing old workforce hampering financial efficiency could also be overblown.

Background

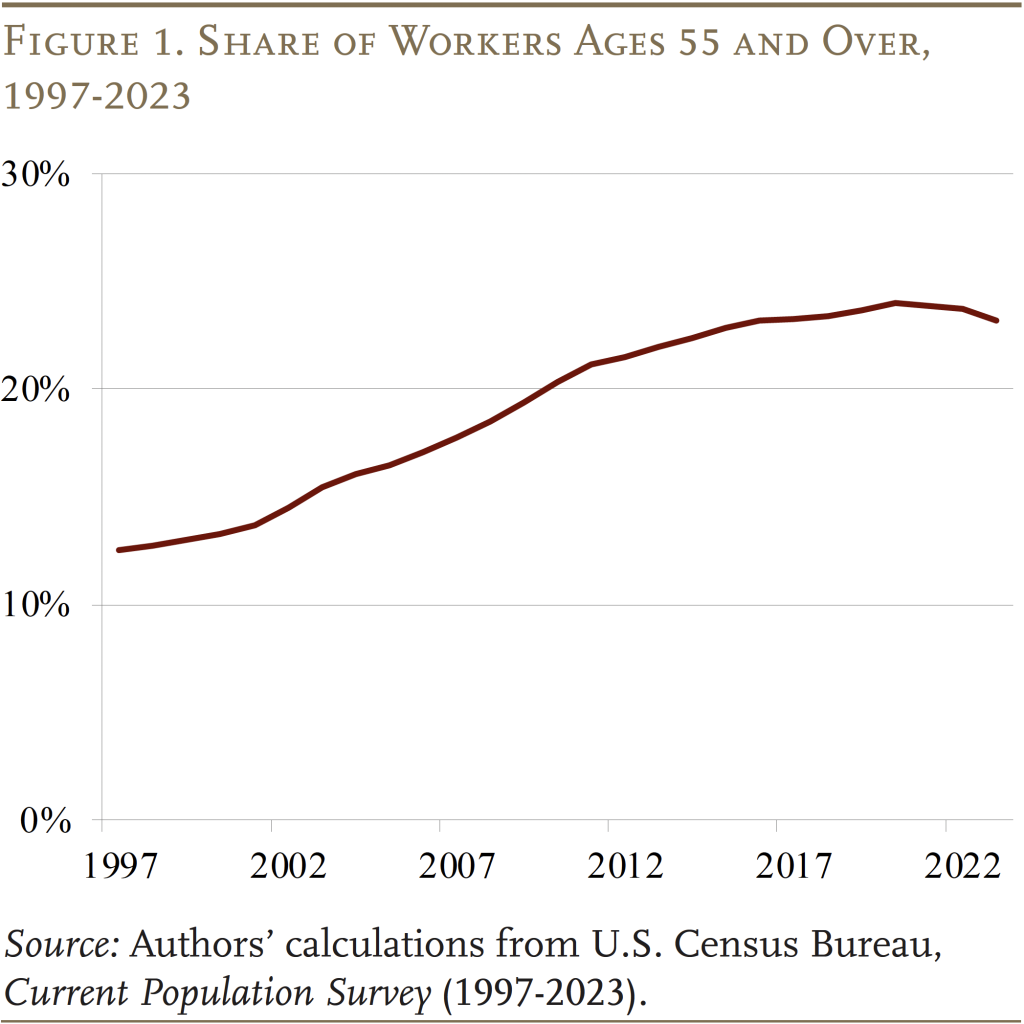

The share of employees ages 55 and over has elevated dramatically over the previous few a long time, doubling since 1997 (see Determine 1). Regardless of this monumental change within the age construction of the workforce, most analysis on the productiveness of older employees is each dated and contradictory. Two research from 1999 attain conflicting conclusions on the affect of employees ages 55 and over; one finds that having a bigger share of such employees reduces a agency’s productiveness, whereas the opposite research finds (statistically insignificant) proof that output could improve with a better share of older employees. Doubtlessly extra regarding, the newest estimates of employee productiveness use knowledge from over 20 years in the past.

As an alternative of quantitative outcomes, latest proof within the U.S. context tends to depend on qualitative assessments or imperfect proxies of productiveness, similar to turnover charges. However meta-analyses of research utilizing oblique measures of efficiency additionally attain diverging conclusions: one finds that superior employee age is detrimental basically, whereas the opposite concludes that age is positively related to work-related efficiency. In the meantime, macroeconomic proof means that, a minimum of on the combination degree, an older workforce slows productiveness development. Considerably extra analysis exists within the European context. Right here too, nevertheless, the conclusions differ broadly.

Information and Methodology

The most important problem in assessing the productiveness and profitability of older employees is entry to knowledge that hyperlink workers to their employers. This info comes from merging three databases. The U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Family Dynamics (LEHD) hyperlinks state administrative unemployment insurance coverage information, IRS employer tax info, and Census knowledge on institutions to supply an correct and complete account of employment and earnings at detailed geographic and trade ranges. The Longitudinal Enterprise Database (LBD) gives knowledge on agency payroll and variety of workers, and the Census’ Enterprise Register (CBR) is a complete itemizing of the placement and trade of all home enterprise institutions. Linking these three datasets makes it attainable to trace companies and institutions over time, whereas observing their revenues and payroll, and the age composition (and different demographics) of their workforces. The info out there for this evaluation span 1997-2014.

The evaluation has two elements. The primary evaluation makes use of a regression equation to estimate the connection between the share of a agency’s employees ages 55 and over and that agency’s productiveness and profitability, and the way these associations differ by trade. Productiveness is outlined as the entire revenues of a agency divided by its workers. Profitability is outlined as how a lot income is generated per greenback of payroll. Companies are divided by trade utilizing customary classifications.

Since having a retirement plan on the agency may enable marginal older employees to retire extra simply, leaving solely extra productive employees, the evaluation controls for plan availability. The evaluation additionally controls for agency measurement and age, and different demographics of the workforce (gender, race/ethnicity, and academic attainment) to make sure the comparability is between corporations with in any other case related workforces. Lastly, the estimated regressions management for geography and secular traits in productiveness.

These standards yield the next equation:

Productiveness (Profitability) = ƒ (% older employees, % prime-age employees, % older employees * % prime-age employees, controls)

The thought experiment is how productiveness and income would change if the share of older employees had been elevated by one proportion level on the expense of lowering the share of employees beneath age 30. This tradeoff between the oldest and youngest employees is sensible for the reason that extra extreme-age employees usually tend to be part-time, much less prone to be strongly hooked up to the employer, and usually have extra elastic labor provide. In conducting this thought experiment, it is very important account for attainable complementarity between older and youthful employees. The estimated relationship between older employees and agency outcomes thus is determined by the prevailing share of prime-age employees who is likely to be complemented or substituted by these older employees. The measure of curiosity is, subsequently, the coefficient on “share older employees” plus the coefficient on the interplay “share of older employees * share of prime-age employees” the place the share of prime-age employees is about equal to the share for the agency’s trade.

Whereas the regression above will present the correlation between the share of older employees and the productiveness and profitability of the agency, it won’t yield a causal estimate of the impact of older employees on productiveness. For instance, if corporations with low productiveness have a tendency to not rent new employees, the estimate will present that older employees scale back productiveness when, actually, it’s low productiveness that results in an older workforce.

Therefore the second a part of the evaluation turns to a quasi-experimental method, utilizing the age construction of the labor market by which the agency is situated as an instrumental variable for the precise share of the workforce 55 and over. The purpose is to separate the composition of the agency’s workforce from the demand for its product to handle the probability that older employees are caught in declining industries, the place employers usually are not hiring younger employees. Some industries, notably manufacturing, don’t appear to have a transparent hyperlink between their geographic location and their product market. Therefore, the quasi-experimental method restricts consideration to single-establishment manufacturing corporations and considers their commuting zones.

Outcomes: Descriptive Estimates of the Worth of Older Employees

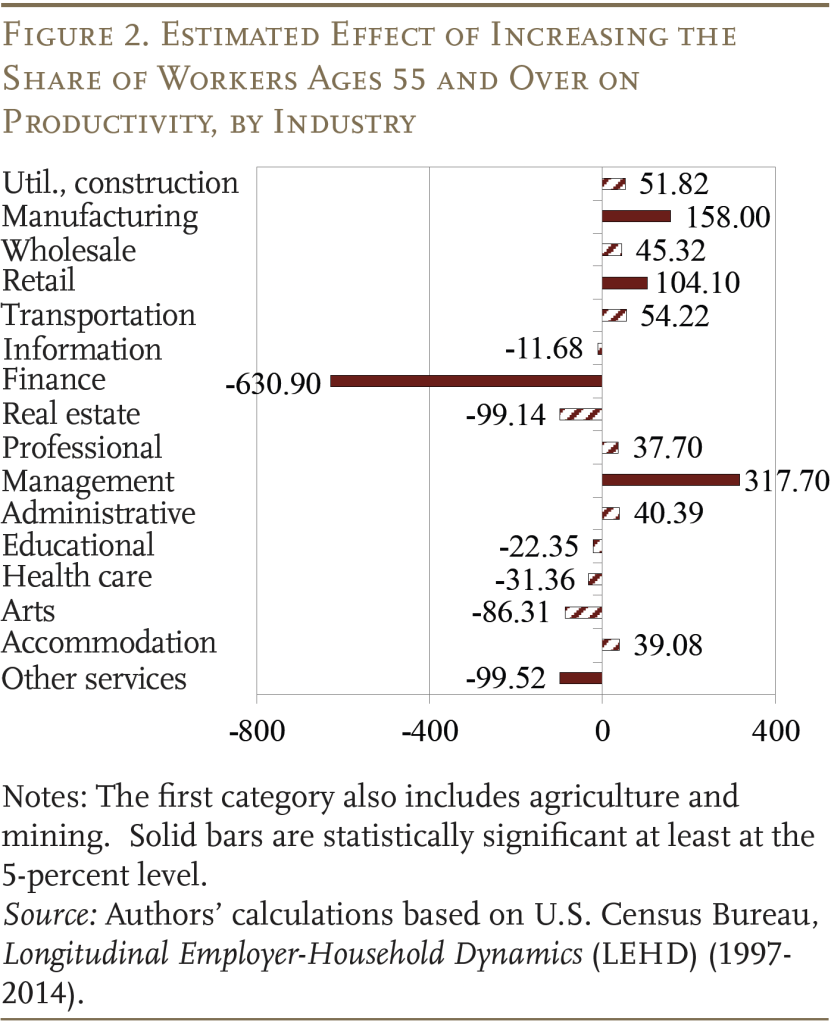

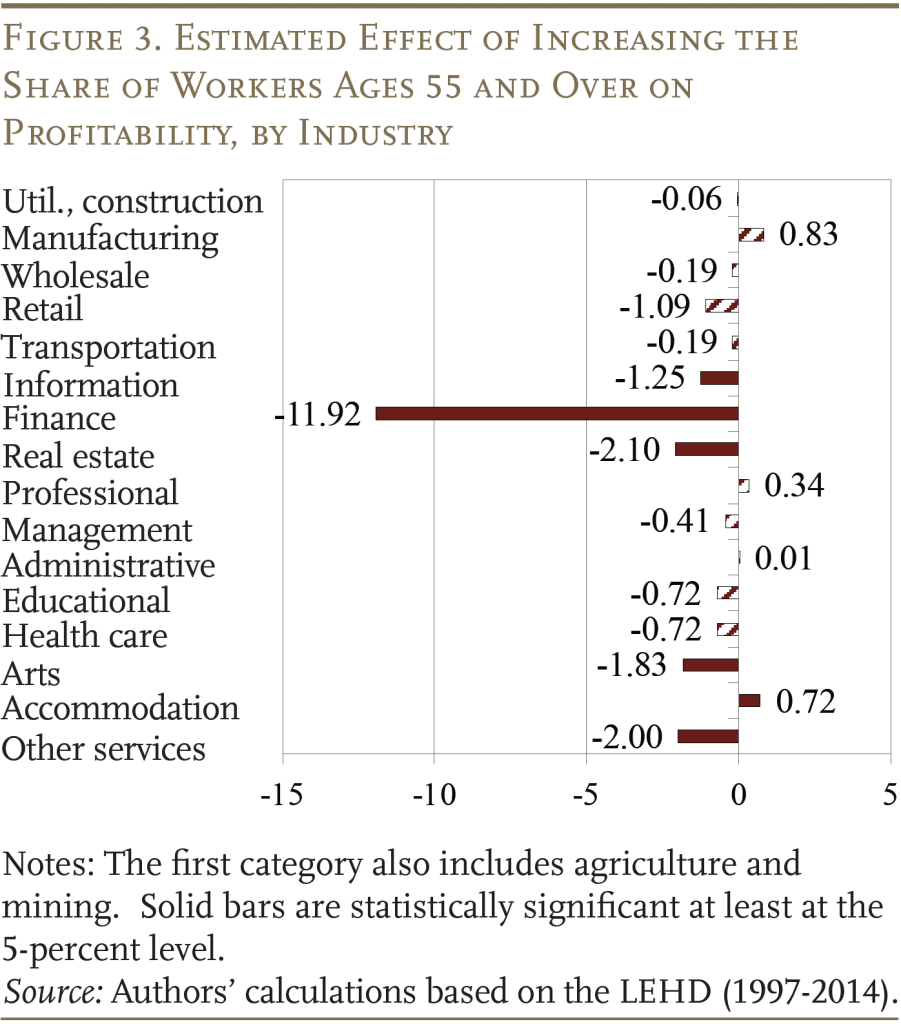

The descriptive outcomes for productiveness don’t present a transparent sample of a adverse relationship with an older workforce (see Determine 2). Excluding finance, which is a transparent outlier (for each productiveness and profitability), different industries are roughly evenly distributed round 0, with these displaying a adverse relationship with age (similar to “different [non-public] companies”) typically greater than counterbalanced by industries displaying a optimistic relationship with age (similar to retail).

The image for profitability is extra lopsided, with the estimates typically indicating {that a} bigger share of older employees is related to decrease income (see Determine 3). The magnitude of the connection is substantial; for a lot of industries, a 1-percentage-point improve within the share of older employees is related to a $1 or extra decline in income to payroll, whereas the imply ratio of income to payroll is $6.2. This sample is in step with a big physique of empirical proof that wages proceed to extend with tenure even after productiveness development has flattened out.

Briefly, older employees seem like as productive as youthful employees, however they price extra. Nonetheless, as famous above, a priority with all these estimates is {that a} declining agency could have a big share of older employees as a result of youthful employees don’t want to enter it. If that’s the case, the connection between the share of older employees and agency efficiency could be adverse, however this relationship wouldn’t imply that an more and more older workforce was inflicting much less profitability. The subsequent part summarizes the outcomes of the quasi-experimental estimation geared toward addressing this concern.

Outcomes: Quasi-Experimental Estimates

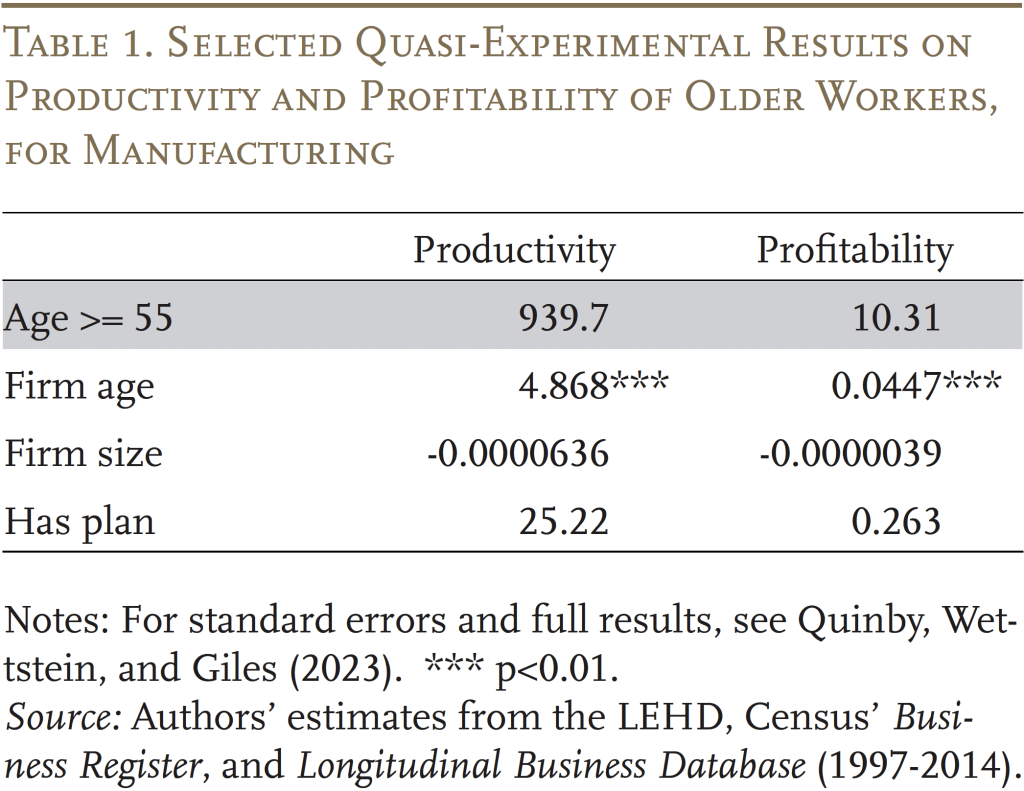

The quasi-experimental outcomes of the worth of older employees in manufacturing assist the speculation that the descriptive outcomes are biased. Mechanically, the outcomes present that the share of the commuting-zone inhabitants ages 55 and over is certainly predictive of the share of older employees within the commuting-zone’s manufacturing institutions. Thus, the evaluation proceeds to make use of the estimated share of the inhabitants ages 55 and over because the instrumental variable.

Chosen outcomes of the second stage of this quasi-experimental process are proven in Desk 1. The important thing discovering is that the share of older employees is just not statistically considerably associated to productiveness or profitability.

Conclusion

Because the working inhabitants ages, a prevalent fear is that this demographic pattern will undermine prospects for financial prosperity. From the narrower perspective of employers, workforce growing old raises the chance that productiveness and profitability might be set again. The proof of age discrimination in hiring means that some employers are being influenced by these fears in sensible administration choices. And advocates for longer working lives should deal with the truth that little proof exists to disprove such fears.

The present evaluation lays out proof based mostly on the newest out there knowledge, for the most important attainable pattern, masking the overwhelming majority of U.S. employment. The findings give cause to hope that, basically, workforce growing old is just not a serious concern for agency productiveness and profitability. Whereas estimates differ by trade, as a complete we discover little proof that older employees are systematically related to decrease productiveness as in comparison with very younger employees. Moreover, a secondary evaluation geared toward addressing problems with reverse causality equally finds no proof that older employees causally scale back productiveness or profitability within the restricted, however necessary, manufacturing sector.

References

Aon Hewitt. 2015. “A Enterprise Case for Older Employees Age 50+: A Have a look at the Worth of Expertise.” Washington, DC: AARP.

Aubert, Patrick and Bruno Crépon. 2006. “Age, Wage and Productiveness: Agency-Degree Proof.” Working Paper.

Backes-Gellner, Uschi and Stephan Veen. 2013. “Constructive Results of Ageing and Age Range in Progressive Firms – Massive-Scale Empirical Proof on Firm Productiveness.” Human Useful resource Administration Journal 23(3): 279-295.

Borsch-Supan, Axel and Matthias Weiss. 2016. “Productiveness and Age: Proof from Work Groups on the Meeting Line.” The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 7(C): 30-42.

Finkelstein, Ruth and Dorian Block. 2015. “10 Benefits of Retaining and Hiring Older Employees.” New York, NY: Columbia College, The Robert N. Butler Getting old Heart and the Mailman College of Public Well being.

Fiorito, Riccardo and Giulio Zanella. 2012. “The Anatomy of the Combination Labor Provide Elasticity.” Evaluate of Financial Dynamics 15: 171-187.

Feyrer, James. 2007. “Demographics and Productiveness.” Evaluate of Economics and Statistics 89(1): 100-109.

Feyrer, James. 2008. “Combination Proof on the Hyperlink Between Age Construction and Productiveness.” Inhabitants and Improvement Evaluate 34: 78-99.

Haltiwanger, John, Henry Hyatt, and Erika McEntarfer. 2017. “Who Strikes Up the Job Ladder?” Working Paper 23693. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Haltiwanger, John, Julia Lane, and James Spletzer. 1999. “Productiveness Variations throughout Employers: The Roles of Employer Measurement, Age, and Human Capital.” American Financial Evaluate 89(2): 94-98.

Haltiwanger, John, Julia Lane, and James Spletzer. 2007. “Wages, Productiveness, and the Dynamic Interplay of Companies and Employees.” Labor Economics 14(3): 575-602.

Hellerstein, Judith, David Neumark, and Kenneth Troske. 1999. “Wages, Productiveness, and Employee Traits: Proof from Plant-Degree Manufacturing Features and Wage Equations.” Journal of Labor Economics 17(3): 409-446.

Ilmakunnas, Pekka and Mika Maliranta. 2016. “How Does the Age Construction of Employee Flows Have an effect on Agency Efficiency?” Journal of Productiveness Evaluation 46: 43-62.

Lovász, Anna and Mariann Rigó. 2013. “Classic Results, Getting old and Productiveness.” Labour Economics 22(C): 47-60.

Maestas, Nicole, Kathleen J. Mullen, and David Powell. 2023. “The Impact of Inhabitants Getting old on Financial Development, the Labor Drive and Productiveness.” American Financial Journal: Macroeconomics 15(2): 306-332.

Mahlberg, Bernhard, Inga Freund, Jesús Crespo Cuaresma, and Alexia Prskawetz. 2013. “The Age-Productiveness Sample: Do Location and Sector Affiliation Matter?” The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 1-2: 72-82.

Malmberg, Bo, Thomas Lindh, and Max Halvarsson. 2008. “Productiveness Penalties of Workforce Getting old: Stagnation or Horndal Impact.” Inhabitants and Improvement Evaluate 34: 238-256.

Munnell, Alicia H. and Gal Wettstein. 2020. “Employer Perceptions of Older Employees – Surveys from 2019 and 2006.” Working Paper 2020-8. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis.

Neumark, David, Ian Burn, and Patrick Button. 2019. “Is It More durable for Older Employees to Discover Jobs? New and Improved Proof from a Discipline Experiment.” Journal of Political Financial system 127(2): 922-970.

Ng, Thomas W. H. and Daniel C. Feldman. 2008. “The Relationship of Age to Ten Dimensions of Job Efficiency.” Journal of Utilized Psychology 93(2): 392-423.

Quinby, Laura D., Gal Wettstein, and James Giles. “Are Older Employees Good for Enterprise?” Working Paper 2023-19. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston School.

Sturman, Michael C. 2003. “Looking for the Inverted U-Formed Relationship Between Time and Efficiency: Meta-Analyses of the Expertise/Efficiency, Tenure/Efficiency, and Age/Efficiency Relationships.” Journal of Administration 29(5): 609-640.

U.S. Census Bureau. Enterprise Register, Longitudinal Enterprise Database, and Longitudinal Employer-Family Dynamics, 1997-2014. Washington, DC.

U.S. Census Bureau. Present Inhabitants Survey, 1997-2023. Washington, DC.

Vandenberghe, Vincent. 2013. “Are Companies Keen to Make use of a Greying and Feminizing Workforce?” Labour Economics 22: 30-46.

[ad_2]