[ad_1]

The temporary’s key findings are:

- Most households within the Nationwide Retirement Threat Index have a superb sense of whether or not they’re on observe for retirement:

- 40 p.c are in fine condition and understand it.

- 20 p.c are in hassle and understand it.

- The remaining are both “not frightened sufficient” or “too frightened.”

- These “not frightened sufficient” usually tend to have larger incomes and should misjudge how a lot their belongings can present.

- Whereas this group is in essentially the most hazard of saving too little, even those that do acknowledge they’re in hassle could not act until prodded.

Introduction

The Nationwide Retirement Threat Index (NRRI) measures the share of working-age households that’s prone to being financially unprepared for retirement. For the reason that Nice Recession, the calculations present that even when households work to age 65 and annuitize all their monetary belongings, together with the receipts from reverse mortgages on their houses, roughly half of households are prone to being unable to keep up their lifestyle.

This temporary examines whether or not households have a superb sense of their very own retirement preparedness – do their expectations match the fact they face? That’s, do households in danger know they’re in danger? Understanding households’ self-assessed retirement preparedness is essential as a result of misperceptions can distort saving behaviors. Households that aren’t frightened sufficient about their retirement revenue could not save sufficient even when they’ve the chance; households which can be too frightened could unnecessarily sacrifice their pre-retirement lifestyle.

The dialogue proceeds as follows. The primary part summarizes the NRRI. The second part compares households’ self-assessed preparedness to the target measure offered by the NRRI to gauge whether or not households have correct perceptions and the way these perceptions have modified over time. The third part identifies the traits of the households with inaccurate perceptions – these which can be both “not frightened sufficient” or “too frightened.” The ultimate part concludes that nearly 60 p.c of self-assessments agree with the NRRI outcomes and that the 40 p.c of households that get it improper achieve this for predictable causes. The problem stays, nevertheless, whether or not unprepared households that acknowledge their state of affairs are any extra more likely to take corrective motion than these that don’t.

The NRRI

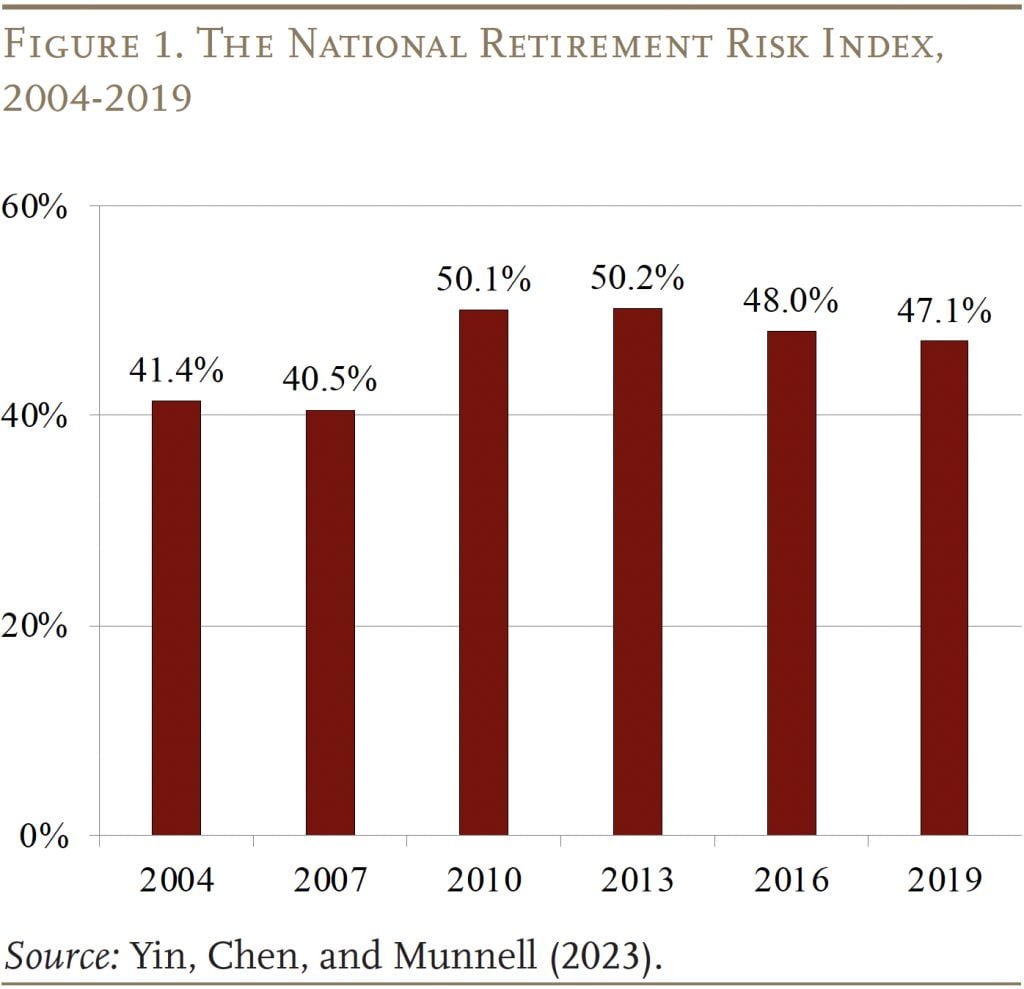

The NRRI is predicated on the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Client Funds (SCF), a triennial survey of a nationally consultant pattern of U.S. households. The Index calculates, for every SCF family, a substitute price – projected retirement revenue as a share of pre-retirement earnings – and compares that substitute price with a goal price derived from a consumption smoothing mannequin. Those that fail to come back inside 10 p.c of the goal are outlined as “in danger,” and the Index experiences the share of all households in danger (see Determine 1).

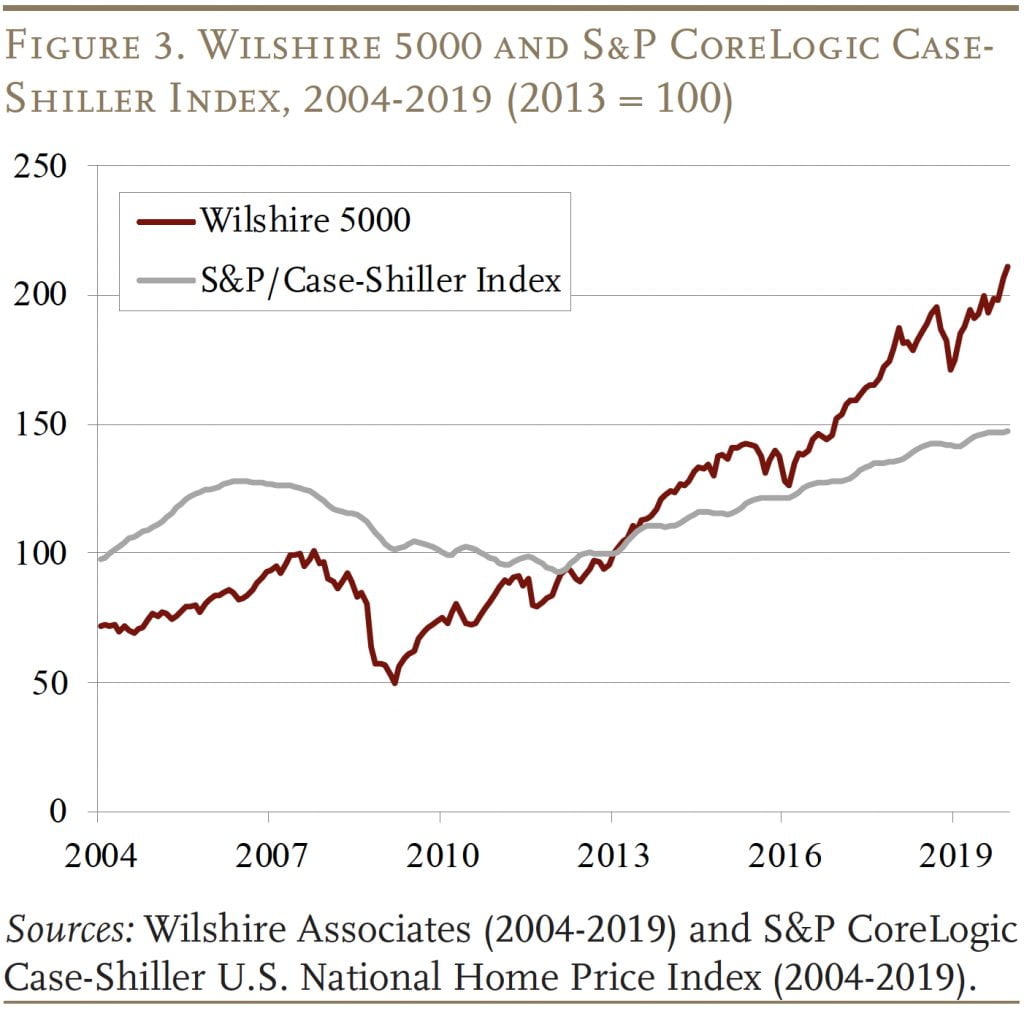

The Index rose considerably between 2007 and 2010 because of the Nice Recession, after which recovered slowly from 2013 to 2019 because the economic system loved low unemployment, rising wages, sturdy inventory market progress, and rising housing costs. The enhancements within the NRRI through the restoration had been modest as a result of some countervailing longer-term developments – such because the gradual rise in Social Safety’s Full Retirement Age (FRA) and the continued decline in rates of interest – which made it tougher for households to realize retirement readiness.

Family Assessments vs. the NRRI

The SCF, which is used to assemble the NRRI, additionally asks every family to price the adequacy of its anticipated retirement revenue. The query’s response scale is from one to 5, with one being “completely insufficient,” three being “sufficient to keep up residing requirements,” and 5 being “very passable.” Thus, any family that solutions one or two considers itself to be in danger.

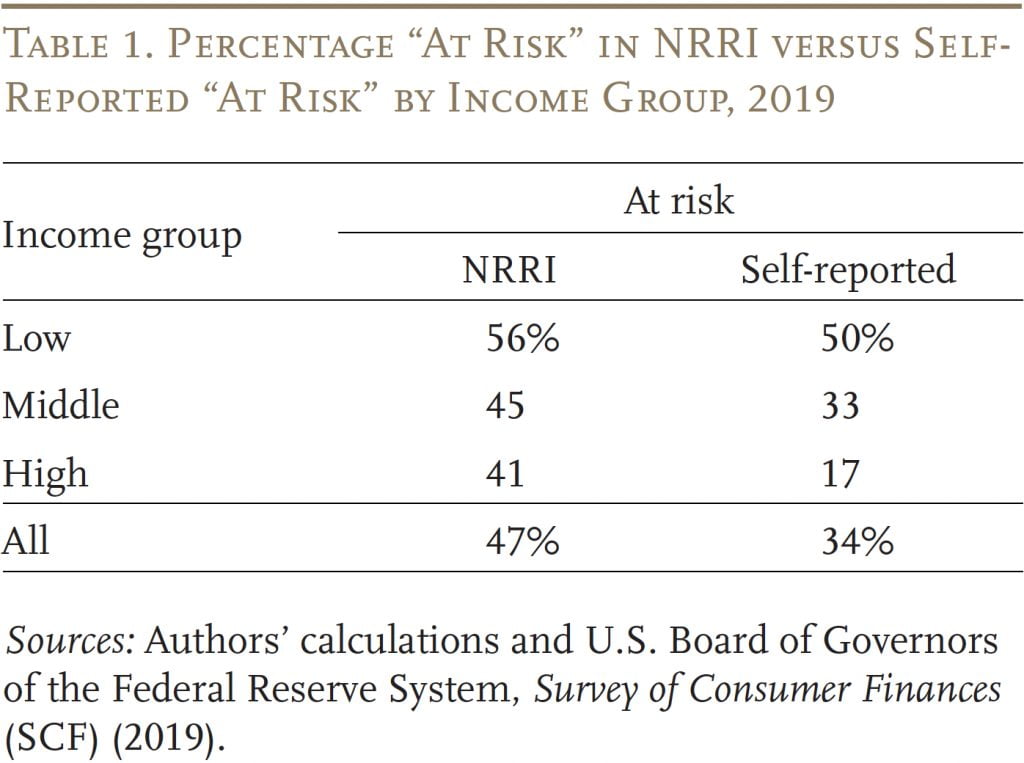

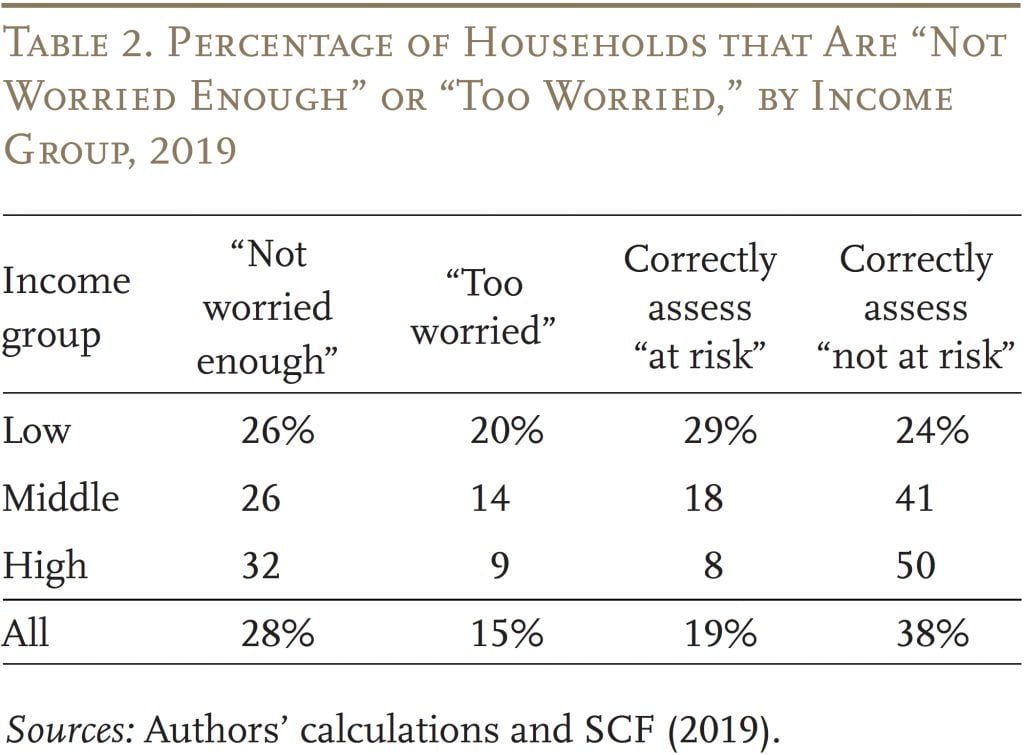

Evaluating households’ self-assessed retirement preparedness to the NRRI’s predictions in 2019 exhibits that households throughout the revenue distribution underestimate their degree of threat (see Desk 1). Solely about one third of households self-report being in danger whereas the NRRI predicts that almost one half are prone to not having sufficient for retirement. Curiously, higher-income households are probably to underestimate their threat.

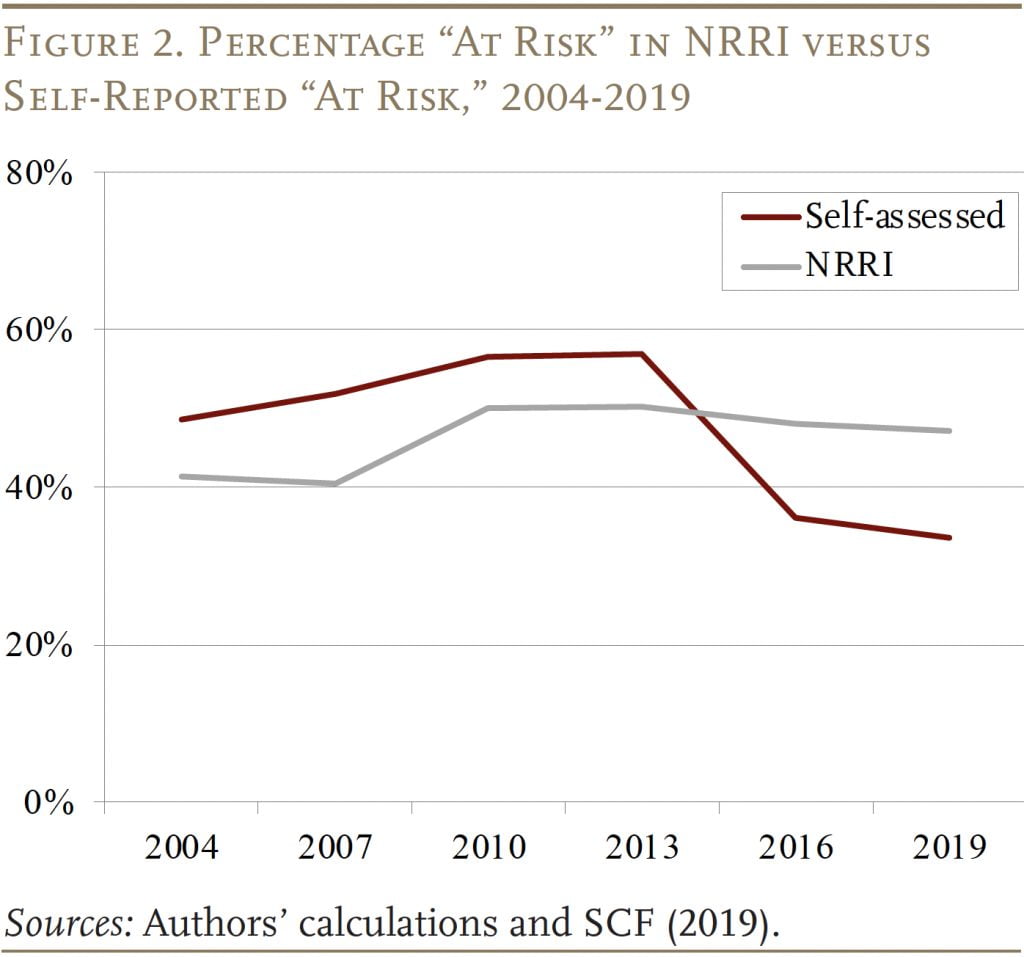

The hole between self-assessed views of enough preparedness and the NRRI has not at all times been so giant. Previous to 2016, the share of households that self-reported being in danger was comparatively according to the NRRI and, in truth, barely larger (see Determine 2). Nevertheless, in 2016, it dropped considerably.

A possible clarification for this sharp decline is that the SCF query modified in 2016. Previous to 2016, households had been requested to evaluate the adequacy of their retirement revenue from Social Safety and employer pensions, together with 401(okay)s/IRAs. After 2016, households had been requested to think about all sources of retirement revenue, which may now embody housing wealth and different monetary belongings. After the change, the share of households ranking their retirement revenue as “insufficient” or “completely insufficient” fell from 57 p.c in 2013 to 36 p.c in 2016 and 34 p.c in 2019, with high-income households reporting the steepest drop. Regardless of the decline, the SCF responses stay throughout the vary proven by different surveys of retirement preparedness – a spread that features the NRRI estimates as properly (see Field).

Field. What Do Different Surveys Present?

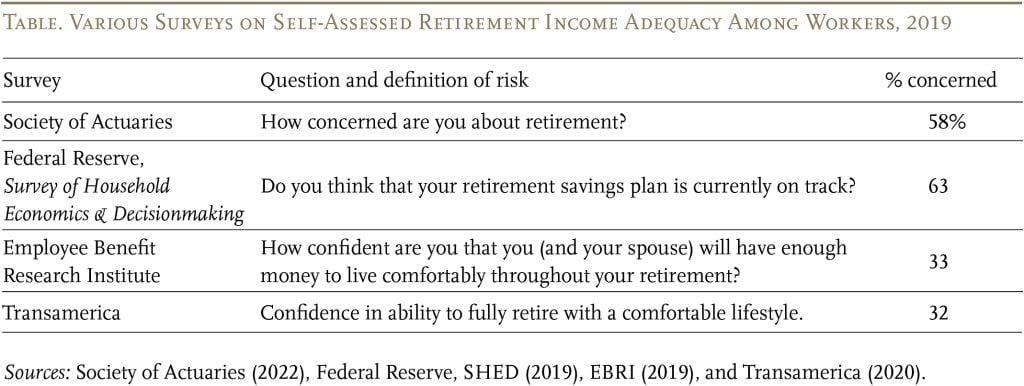

Curiously, different surveys present a spread of outcomes that bracket each the SCF and NRRI numbers (see Desk).

Consultants level out that the wording of the query issues. Particularly, destructive or constructive phrasing can influence responses as a result of acquiescence bias, the place respondents agree with the query requested. Surveys by which a excessive share of households report concern for his or her retirement revenue use destructive or impartial phrases like “involved” or “on-track,” whereas surveys that report a low share use constructive phrases like “assured/confidence.”

Just like the revised SCF query, the NRRI contains housing and monetary belongings when evaluating whether or not a family is in danger. So the sharp decline in self-assessed threat within the SCF after the query change means that households are extra optimistic in regards to the quantity of revenue their housing and non-retirement belongings can present than the NRRI predicts. This optimism, notably amongst higher-income households, could also be as a result of a powerful rebound of the housing and inventory markets throughout this era (see Determine 3).

When evaluating particular person family assessments with the NRRI, 28 p.c assume they don’t seem to be in danger whereas the NRRI predicts they’re (this group is “not frightened sufficient”), and 15 p.c assume they’ll fall brief whereas the mannequin predicts they’ll have sufficient (“too frightened”) (see Desk 2). Outcomes by revenue present that high-income households – maybe overreacting to the influence of the sturdy economic system on housing and inventory costs – are the probably to be “not frightened sufficient” and low-income households are the probably to be “too frightened.” The remaining 57 p.c get it proper, with 19 p.c appropriately ranking they’re in danger and 38 p.c appropriately ranking they don’t seem to be in danger.

What Explains Misperceptions?

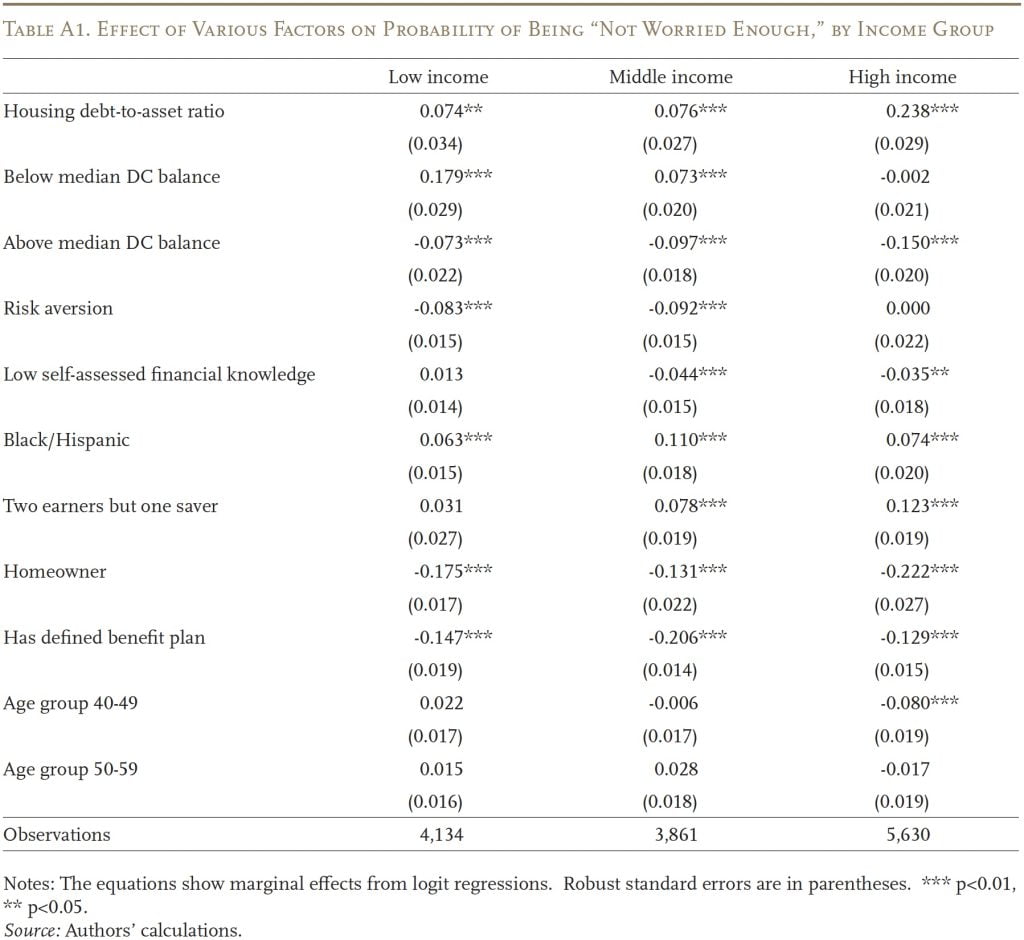

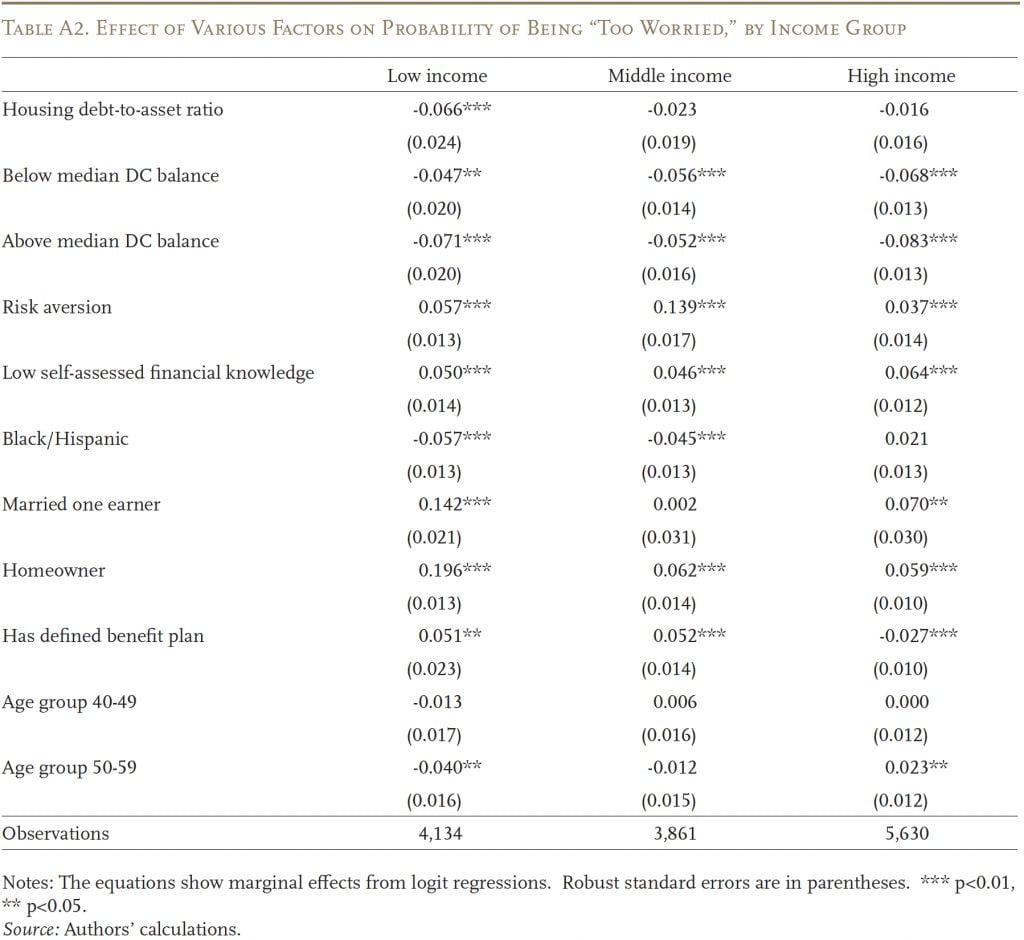

The query is what traits are related to a family being “not frightened sufficient” or “too frightened,” versus getting it proper. The evaluation makes use of regressions to clarify the chance of households ending up in a given class utilizing quite a lot of components, together with: retirement plan participation and account stability, homeownership and housing wealth, threat aversion, self-assessed monetary data, training, family kind, race/ethnicity, and age. The evaluation is performed individually for the low-, middle-, and high-income households as a result of the significance of the explanatory variables could differ throughout the revenue distribution. The key causes for being “not frightened sufficient” or “too frightened” are summarized under. Full outcomes can be found within the Appendix.

Main Causes for “Not Fearful Sufficient”

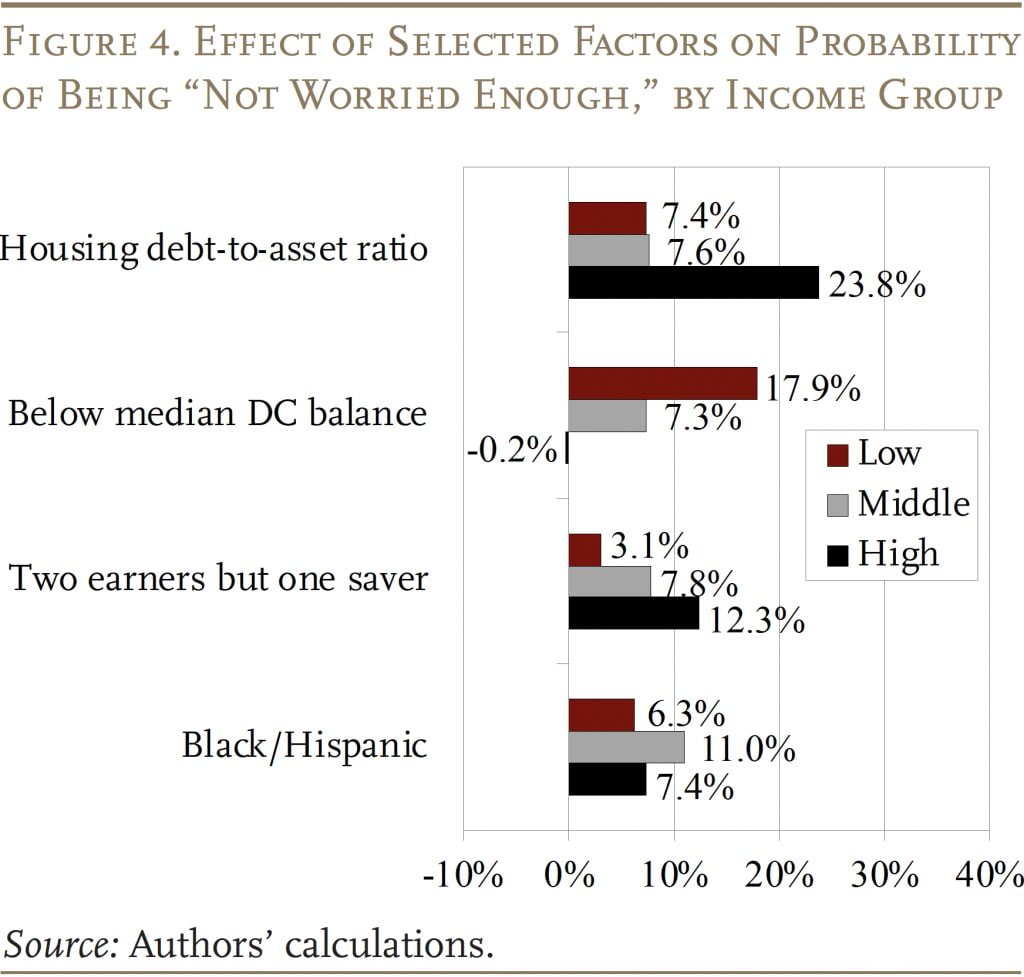

Conceptually, households that had been overly optimistic in regards to the financial restoration or overestimated how a lot revenue their belongings may present could also be extra more likely to be “not frightened sufficient.” Their overconfidence could make them underestimate potential dangers. Due to this fact, it’s not stunning that households with larger housing debt-to-asset ratios, comparatively low asset balances in 401(okay)s and different outlined contribution (DC) plans, and two earners however just one saver had been extra more likely to be “not frightened sufficient” (See Determine 4).

Housing debt-to-asset ratio. Because the housing market improved, households could have been comforted by the rising worth of their asset, with out contemplating how a lot they nonetheless owed. The constructive relationship between the housing debt-to-asset ratio and the “not frightened sufficient” group is particularly sturdy for high-income households, who are likely to personal dearer houses.

Under median DC stability. Equally, the hazard with DC plan belongings is “wealth phantasm.” That’s, $100,000 seems like some huge cash to many individuals despite the fact that it offers solely about $617 monthly in retirement revenue. This wealth phantasm could have been exacerbated by the sturdy market efficiency. Having solely a modest DC stability is related to the next chance of being “not frightened sufficient” for low and middle-income households.

Two earners however one saver. Many dual-earner households could not understand they must exchange each spouses’ earnings to keep up their lifestyle in retirement. So, not surprisingly, dual-earner households the place just one partner has a retirement plan usually tend to be “not frightened sufficient.” This chance additionally will increase with revenue as a result of Social Safety replaces a smaller share of pre-retirement revenue for prime earners.

Black/Hispanic. Black and Hispanic households are additionally extra more likely to be “not frightened sufficient,” maybe as a result of racial/ethnic gaps in monetary literacy.

Main Causes for “Too Fearful”

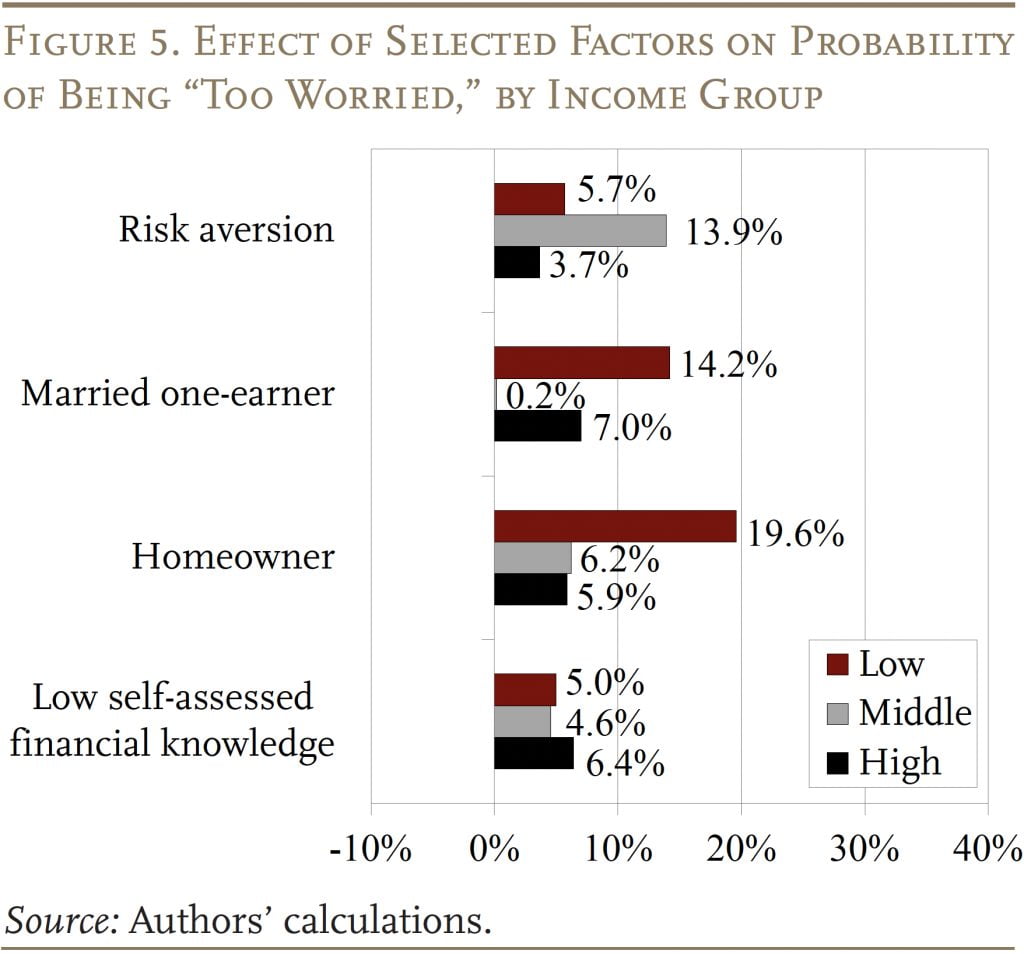

In contrast to overly optimistic households, those that are “too frightened” are usually not conscious of how a lot revenue they’ll have in retirement and maybe have much less optimism within the asset markets. Traits that seize these components – corresponding to threat aversion, married one-earner households, home-owner, and low self-assessed monetary data – predicted households’ chance of being “too frightened” (see Determine 5).

Threat aversion. Households who’re threat averse could be extra conservative when judging their monetary state of affairs and fewer more likely to be swayed by optimism within the asset markets. Due to this fact, it’s not stunning that risk-averse households usually tend to be “too frightened.”

Married one-earner. Single-earner households could not take account of Social Safety’s spousal profit – equal to 50 p.c of the good thing about the working partner – when evaluating their retirement revenue. Maybe because of this, married low-income households with just one earner have the next chance of being “too frightened.”

House owner. Owners usually tend to be “too frightened” as a result of they don’t plan to faucet their dwelling fairness to assist common consumption in retirement. The impact is particularly giant for low-income owners as a result of their dwelling represents a a lot larger portion of their complete web price.

Low self-assessed monetary data. Households that price themselves as having low monetary data could also be much less assured or conscious of their monetary state of affairs. Curiously, these households are doing higher than they assume, as they’re extra more likely to be “too frightened.”

General, the outcomes counsel that households with incorrect perceptions get it improper for predictable causes. Just a little training in regards to the worth of varied sources of retirement revenue may cut back the scale of the “too frightened” group.

Conclusion

Regardless of analysis displaying households have giant gaps in monetary data, practically three out of 5 have a superb intestine sense of their monetary state of affairs. This share has remained comparatively fixed regardless of a 2016 change within the SCF survey. Nevertheless, classifying households by the accuracy of their perceptions about retirement safety doesn’t reply the query of whether or not they’re more likely to take remedial motion. Households which can be “not frightened sufficient” are the least more likely to change their saving or retirement plans. This group accounts for 28 p.c of households, so a good portion of the inhabitants must get a greater evaluation of their retirement revenue wants. The extra one-fifth of households that do perceive their plight might have much less convincing to behave, however they nonetheless should act.

References

Billiet, Jaak B. and McKee J. McClendon. 2000. “Modeling Acquiescence in Measurement Fashions for Two Balanced Units of Gadgets.” Structural Equation Modeling 7(4): 608-628.

Worker Profit Analysis Institute. 2019. “2019 RCS Truth Sheet #1 Retirement Confidence.” Washington, DC.

Goldstein, Daniel G., Hal E. Hershfield, and Shlomo Benartzi. 2016. “The Phantasm of Wealth and Its Reversal.” Journal of Advertising Analysis 53(5): 804-813.

Jackson, Douglas N. 1959. “Cognitive Power Stage, Acquiescence, and Authoritarianism.” The Journal of Social Psychology 49(1): 65-69.

Sanzenbacher, Geoffrey T. and Wenliang Hou. 2019. “Do People Know When They Ought to Be Saving for a Partner?” Concern in Temporary 19-5. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston School.

Society of Actuaries. 2022. “2021 Retirement Threat Survey Report of Findings.” Schaumburg, IL.

Transamerica Heart for Retirement Research. 2020. “Retirement Safety Amid COVID-19: The Outlook of Three Generations.” twentieth Annual Transamerica Retirement Survey of Employees. Cedar Rapids, IA.

U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Survey of Client Funds, 2004-2019.

U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Survey of Family Economics and Decisionmaking, 2019.

Welkenhuysen-Gybels, Jerry, Jaak Billiet, and Bart Cambré. 2003. “Adjustment for Acquiescence within the Evaluation of the Assemble Equivalence of Likert-Sort Rating Gadgets.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 34(6): 702-722.

Yin, Yimeng, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H. Munnell 2023. “The Nationwide Retirement Threat Index: Model 2.0.” Concern in Temporary 23-10. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston School.

Appendix

[ad_2]